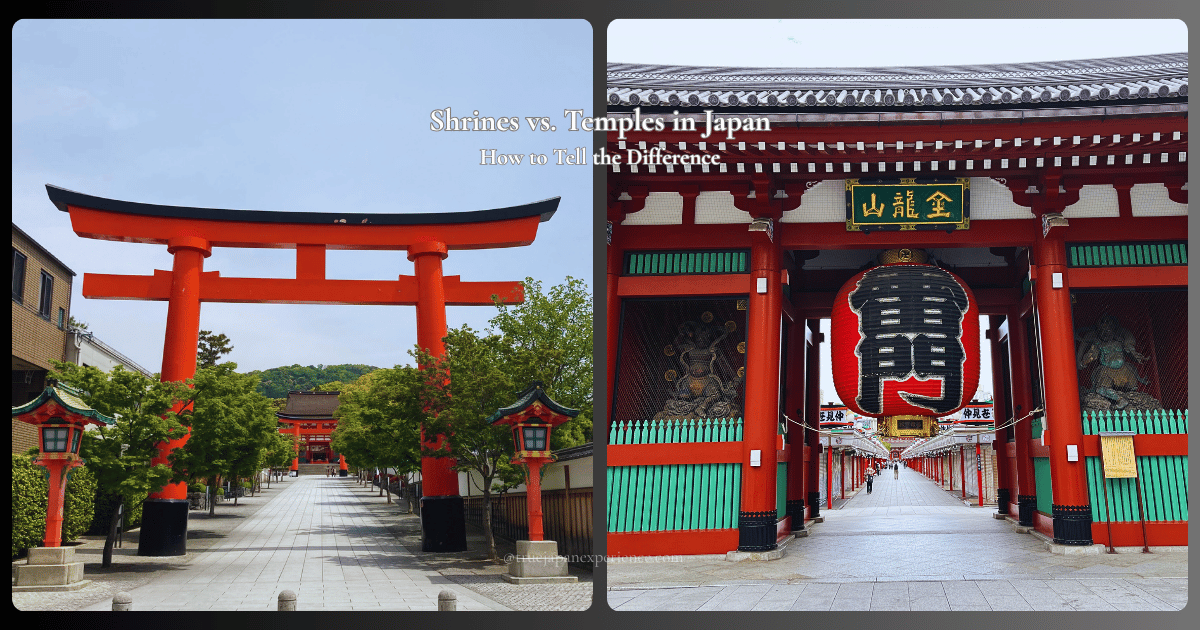

When visiting Japan, you’ll encounter countless beautiful places of worship — but not all are the same. Some are shrines, while others are temples.

Understanding the difference can help you enjoy your visit more deeply and respectfully.

At a glance, shrines and temples may look similar, especially because of Japan’s long history of blending religious traditions. Let’s explore what sets them apart — and why it matters.

Shrines and Temples in Japan: Different Religions, Different Beliefs

When exploring Japan’s spiritual traditions, you’ll encounter two main types of sacred sites: shrines and temples.

Although they may look similar, they are deeply rooted in two different religions — Shinto, Japan’s ancient nature-based belief, and Buddhism, which came from India through Asia in the 6th century.

These religious roots influence everything from architecture and rituals to the way people pray.

Understanding the difference helps you connect more meaningfully with these sacred places — and avoid some common mix-ups along the way.

Shrines (Jinja) – Sacred Sites of Shinto

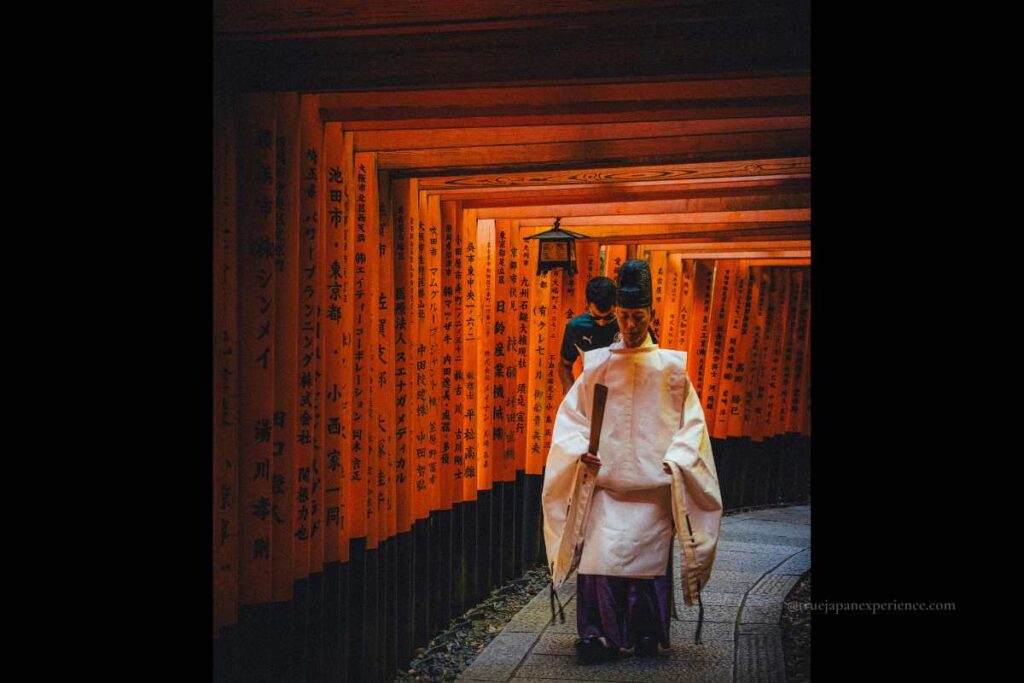

A Shinto priest walks through the iconic torii gates at Fushimi Inari Shrine — a symbol of sacred transition in Shinto belief.

Shrines are places of worship in Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion that honors kami — divine spirits believed to reside in natural elements like mountains, rivers, trees, animals, and even objects.

Unlike Western concepts of “gods,” kami are not all-powerful beings but rather sacred presences that influence everyday life and the natural world.

Each shrine is dedicated to one or more specific kami. You might find shrines devoted to the sun goddess Amaterasu, the god of learning, the deity of safe travel, or even local guardian spirits unique to the area.

One key feature of many shrines is the goshintai — a sacred object housed within the inner sanctuary (honden) that represents the presence of the kami.

This object is usually hidden from view and may be something symbolic, like a mirror, sword, or stone.

However, not all shrines have a goshintai in the form of a physical object.

In some cases, a natural feature itself is worshipped as the kami, such as a mountain, rock, tree, or even a waterfall.

For example, Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara has no main hall; instead, worshippers pray toward Mount Miwa, which is considered the sacred body of the deity.

This deep reverence for nature is one of the defining features of Shinto — the belief that the divine can be found not only in holy artifacts, but in the natural world itself.

This object — often a mirror, sword, stone, or another symbolic item — is believed to contain or represent the presence of the kami. It is never shown to the public, and even the priests may not view it directly.

Before entering a shrine, visitors pass through a torii gate, marking the boundary between the ordinary world and the sacred space.

The path leading to the shrine (called the sando) is often lined with trees or lanterns, creating a serene, reverent atmosphere.

Rather than focusing on doctrines or scriptures, Shinto emphasizes ritual, purity, and connection with nature and community. It’s a religion deeply woven into Japanese culture — not only as faith, but as custom and identity.

While many shrines enshrine a sacred object inside the main hall (honden), some — like Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara — do not have a honden at all.

Instead, the natural feature itself, such as a mountain, is worshipped as the kami.

The worship hall (haiden) of Ōmiwa Shrine in Nara. This shrine has no main sanctuary building; instead, the sacred mountain behind it, Mount Miwa, is revered as the kami itself.

Temples (Otera) – Places of Buddhism

Temples in Japan are sacred sites of Buddhism, a religion that came to Japan from India via China and Korea in the 6th century.

While Shinto focuses on nature and everyday rituals, Buddhism offers teachings on life, death, and how to overcome suffering.

Each temple enshrines one or more Buddhist deities, which may include Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, or other revered figures depending on the temple’s sect and historical background.

For example, some temples venerate Amida Nyorai (Amitabha), while others may focus on Kannon (Avalokiteshvara) or Yakushi Nyorai (the Healing Buddha).

The main hall (hondō) houses the principal image (honzon) of worship, which varies greatly from temple to temple.

The Great Buddha (Daibutsu) of Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara. This colossal bronze statue represents Vairocana Buddha and is one of the largest and most revered Buddhist icons in Japan.

Japanese Buddhism has developed into many distinct schools, including:

Hossō, known as one of the oldest surviving sects

Shingon and Tendai, influential in the Heian period

Zen (Sōtō and Rinzai), Pure Land (Jōdo and Jōdo Shinshū), and Nichiren, which flourished from the Kamakura period onward

In addition to these, there are many other sects and sub-schools, each with their own unique history and spiritual focus.

Some are highly philosophical, while others emphasize devotional practices or community engagement.

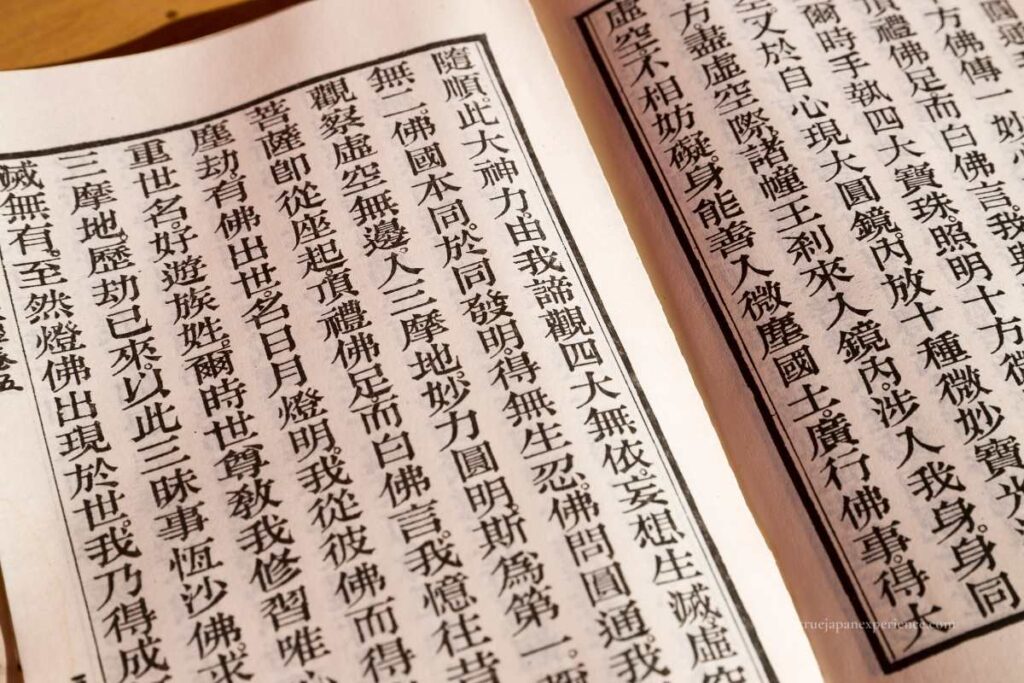

Each tradition has its own teachings, practices, scriptures, and rituals, ranging from esoteric ceremonies to chanting, sutra copying, or community services.

Some temples offer experiences like zazen (seated meditation), while others focus on devotional chanting or educational programs. Not all temples emphasize meditation — and not all follow the same path to enlightenment.

The atmosphere at a temple can vary, but many are designed to be peaceful and reflective spaces, often featuring gardens, pagodas, and incense.

Visitors may come to pray, make offerings, participate in memorial services, or simply find a quiet place to connect with something beyond the everyday.

Buddhist temples often use incense, sutras, and sacred statues in their rituals.

Below is an example of a traditional Buddhist scripture:

A traditional Buddhist sutra, often chanted during temple rituals.

Shrine vs. Temple Architecture: Gateways and Sacred Spaces

Whether you’re strolling through a quiet mountain path or navigating a bustling city street, you’re bound to come across religious buildings in Japan. But how can you tell if it’s a Shinto shrine or a Buddhist temple?

One of the easiest ways to spot the difference is by looking at the gateways and architectural features.

Shrines and temples follow different design principles, rooted in their religious beliefs and cultural functions. From torii gates to pagodas, each element tells a story.

Let’s explore how their structures reflect the spirit of Shinto and Buddhism — and how you can recognize them at a glance.

Shrines Have “Torii” Gates – Marking the Sacred Entrance

One of the most iconic and instantly recognizable features of a Shinto shrine is the torii gate.

Standing tall at the entrance to a shrine, the torii marks the boundary between the everyday world (俗界 / zokkai) and the sacred space (神域 / shin’iki) where the kami dwell.

Passing through a torii is a symbolic act of purification. It signifies your intention to leave behind the mundane and approach the divine with respect.

This is why many visitors bow before passing through, acknowledging the transition into a spiritually significant place.

Torii come in many forms,Torii come in many forms, but the most common are painted in vermilion red.Others may be left unpainted, made of wood, stone, or even metal, depending on the shrine’s history and location.

Some torii are elaborate and grand, such as the giant floating torii of Itsukushima Shrine in Hiroshima. Others are simple and rustic, standing quietly in mountain forests or by sacred waterfalls.

There are also various styles of torii, each with its own architectural features — such as:

Myōjin torii (curved upper lintel, commonly seen)

Shinmei torii (straight and simple)

Ryōbu torii (associated with syncretic Shinto-Buddhist sites)

At some shrines, multiple torii are aligned in rows, forming tunnels of sacred gates.

A famous example is Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto, where thousands of red torii stretch across the mountainside — each donated by individuals or businesses hoping for blessings.

⇒If you’re curious about this stunning site and its deep connection with fox spirits and prosperity, check out our full guide: Fushimi Inari Taisha – Kyoto’s Shrine of Foxes and Torii Gates.

Ultimately, torii are not just physical structures — they are symbols of purity, spiritual threshold, and Shinto identity.

Even outside of religious contexts, the torii has become a universal symbol of Japanese culture and tradition.

Temples Have “Sanmon” Gates – Welcoming the Seeker Inside

The Great South Gate (Nandaimon) of Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara. This imposing wooden structure is a typical example of a sanmon gate found at major Buddhist temples.

Buddhist temples are typically entered through a sanmon (literally, “mountain gate”), a grand wooden structure that serves as the formal entrance to the temple grounds.

These gates are often impressive in size and design, symbolizing the boundary between the everyday world and the sacred path of Buddhist practice.

Many sanmon gates feature two fierce guardian statues, known as Nio, placed on either side to protect the temple and ward off evil.

These muscular figures — one with an open mouth (Agyō) and the other with a closed mouth (Ungyō) — represent birth and death, the beginning and end of all things.

The gate itself is not just an entryway, but a symbolic invitation to leave behind worldly attachments and enter a space of calm and contemplation.

In some temples, the sanmon has upper levels that once served as watchtowers or lecture halls for monks.

It’s worth noting that due to Japan’s long tradition of blending Shinto and Buddhism, some temple complexes may also include torii gates, or be located near Shinto shrines.

Even locals sometimes can’t tell the difference — so don’t worry if the lines seem blurred. It’s part of Japan’s rich spiritual history.

How to Pray at Shrines and Temples: What’s the Difference?

When visiting Japan, many travelers find themselves wondering how to properly pray at religious sites.

But did you know that the way you pray at a Shinto shrine is quite different from how you pray at a Buddhist temple?

These differences aren’t just about form — they reflect the underlying beliefs and values of each tradition.

Understanding the correct etiquette not only shows respect, but also allows you to connect more meaningfully with Japan’s spiritual culture.

Let’s take a closer look at how the two practices differ — and why it’s perfectly okay if you’re still learning.

At a Shrine: Clap and Bow (2-2-1 Ritual)

Children praying at a Shinto shrine. The saisen box in front is used to offer coins before performing the 2-2-1 ritual of bowing and clapping.

When visiting a Shinto shrine, there is a unique and respectful way to offer your prayers.

The standard practice is known as the “2-2-1 ritual” — short for two bows, two claps, one final bow.

Here’s how to do it step by step:

1. Bow deeply twice. This shows your humility and respect as you stand before the kami (Shinto deity).

2. Clap your hands twice. This part is called kashiwade. The sound of your claps is believed to help call the attention of the kami to your presence.

3. Place your hands together and silently make your wish or prayer. You can close your eyes if you like. This moment is for offering your gratitude or request.

4. Bow deeply once more. This final bow completes the ritual and shows your appreciation.

This is the most common way to pray at Shinto shrines, but keep in mind that some shrines have unique traditions — for example, Izumo Taisha uses a “two bows, four claps, one bow” ritual.

If you’re unsure what to do, don’t worry — many shrines display illustrated instructions near the offering box, or you can simply observe how others around you are praying.

At a Temple: Quietly Gassho (Press Your Palms)

At Buddhist temples in Japan, the way to pray is different from shrines.

Here, the typical practice is to quietly show reverence with a bow and gassho — placing your palms together in front of your chest.

1.Bow once. This is a respectful gesture before approaching the sacred space.

2.Press your hands together (gassho) and silently offer your prayer or thought. No clapping is used.

This quiet, non-verbal form of worship reflects the Buddhist emphasis on mindfulness, respect, and inner reflection.

While this is a common method, prayer customs can vary slightly depending on the temple or sect. If you’re unsure, look for posted instructions or observe how others are praying.

Why Shrines and Temples in Japan Can Be Hard to Tell Apart

Up to this point, we’ve looked at the architectural features and prayer customs that help distinguish shrines from temples in Japan.

However, despite these clear differences, it’s not always easy to tell them apart — and there’s a good reason for that.

For nearly a thousand years, Shinto and Buddhism were not separate in practice.

Instead, they coexisted and even fused together under a religious tradition known as Shinbutsu-shūgō, or the syncretism of kami and Buddhas.

This deep historical entanglement continues to shape the spiritual landscape of Japan today.

The Era of Shinbutsu-Shūgō – When Shrines and Temples Were One

In ancient Japan, Shinto shrines — rooted in the native worship of kami, or spirits of nature and place — had long been a part of daily life.

But in the 6th century, Buddhism arrived from India via China and Korea, introducing new teachings, rituals, and sacred imagery.

Rather than replacing existing beliefs, Buddhism gradually merged with Shinto in a process known as Shinbutsu-shūgō, or the syncretism of kami and Buddhas.

For centuries, it was common to find shrines and temples built together on the same grounds, with people worshipping both Shinto kami and Buddhist figures side by side.

This era of religious fusion gave rise to unique sacred spaces, shared rituals, and hybrid architecture — all of which helped shape a spiritual tradition that was distinctly Japanese.

Shrines and temples often:

・Shared the same sacred grounds

・Held joint rituals and festivals

・Even enshrined both kami and Buddhist deities in the same space

Even in modern times, some traditional Japanese households — especially in rural areas or in families with long-standing ancestral traditions — still reflect this blended spirituality.

It’s not uncommon to see both a Shinto kamidana (a household altar for the gods) and a Buddhist butsudan (an altar for honoring ancestors) in the same home.

So if you ever find yourself standing before a sacred gate or hall in Japan and wondering:

“Is this a shrine, or a temple?”

you’re not alone.

Even today, after the formal separation of the two religions, that lingering sense of overlap remains — a reflection of how Japanese spirituality values harmony over rigid divisions.

What Changed? – Shinbutsu Bunri in the Meiji Era

Until the late 19th century, many shrines and temples in Japan existed as one — sharing grounds, rituals, and even clergy under the system of Shinbutsu-shūgō, the syncretic blending of Shinto and Buddhism.

But in 1868, with the beginning of the Meiji era, the government issued the policy of Shinbutsu Bunri (the separation of kami and Buddhas).

The goal was to establish Shinto as the official state ideology, and to clearly distinguish it from Buddhism, which was seen as a foreign religion.

As a result, many shrine-temple complexes were forced to choose which identity to retain — either as a Shinto shrine or as a Buddhist temple. The “other” identity had to be removed.

This process involved a number of drastic changes:

In many cases, these changes were carried out rapidly and with little regard for historical or artistic value, leading to the destruction of countless cultural assets.

Today – A Blend of Traditions Lives On

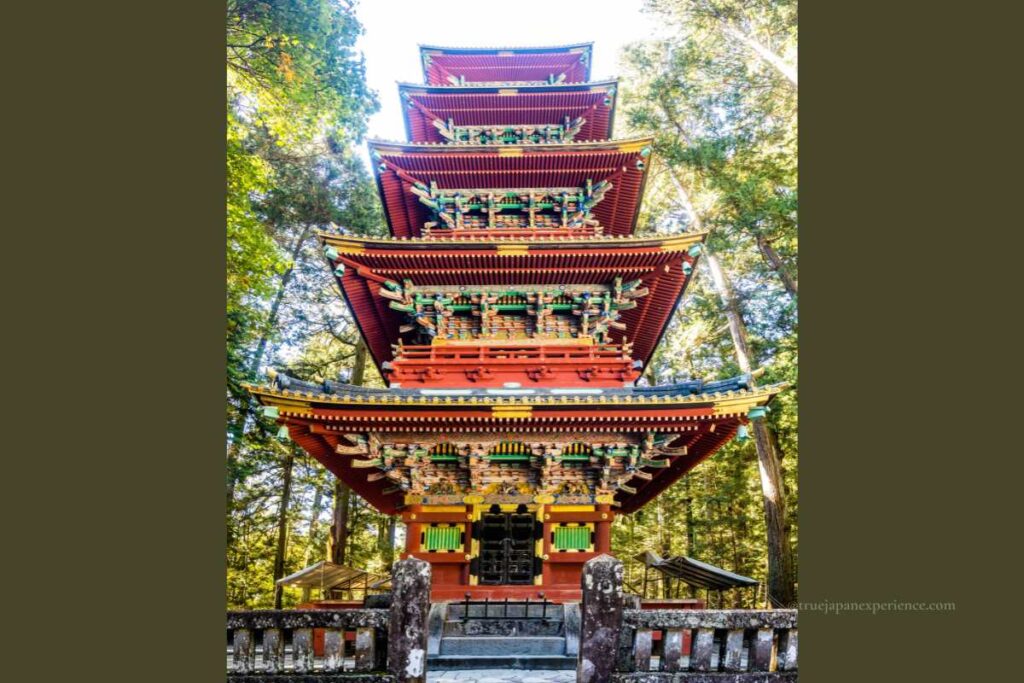

Nikkō Tōshō-gū is a Shinto shrine dedicated to Tokugawa Ieyasu, yet it features a five-story pagoda — a structure more commonly associated with Buddhist temples.

This blend of elements reflects the historical practice of Shinbutsu-shūgō, when shrines and temples shared space and style.

The five-story pagoda at Nikkō Tōshō-gū Shrine. Although a Shinto shrine, it preserves Buddhist architectural elements — a legacy of Japan’s long history of religious syncretism.

Although shrines and temples were officially separated during the Meiji era, the legacy of Shinbutsu-shūgō — the blending of Shinto and Buddhism — can still be seen across Japan today.

This is because the government’s separation policy, while strict, was not uniformly applied in every case.

In many regions, structures and traditions that held deep cultural or historical value were preserved, thanks to local resistance, community ties, or their recognition as important cultural assets.

For example:

・Nikkō Tōshō-gū, a Shinto shrine dedicated to Tokugawa Ieyasu, features a five-story pagoda, an unmistakably Buddhist architectural element. It remains today as a symbol of the syncretic architecture once common across the country.

・In Asakusa, Tokyo, you’ll find Sensō-ji Temple and Asakusa Shrine standing side by side. They share the same historical roots and continue to cooperate during festivals — a living reminder of their once-unified past.

If you’re planning to visit, don’t miss our guide to Sensō-ji Temple.

・The Usa-Kunisaki region in Kyushu is known for preserving some of the most deeply rooted examples of Shinbutsu-shūgō. Here, religious practices and architectural forms reflect centuries of coexistence.

・At Mount Haguro in Yamagata, part of the Dewa Sanzan sacred area, traditions of mountain asceticism continue to blend Shinto and Buddhist elements, despite institutional separation.

In some cases, even sacred Buddhist statues removed from shrines during the separation were relocated to nearby temples and preserved. A famous example is the Eleven-faced Kannon, once enshrined at Ōmiwa Shrine, now safely housed at Shōrin-ji Temple and designated a National Treasure.

These examples show that, even after the official separation of Shinto and Buddhism, some blended traditions and architectural features still remain in various parts of Japan.

That’s why, even today when shrines and temples are once again clearly separated as originally intended,

you might still find yourself wondering:

Is this a shrine, or a temple?

Final Thoughts – Which Should You Visit?

If you’ve read this far, you’ve probably realized that shrines and temples in Japan are both deeply meaningful — but also deeply different.

To help you remember the key differences, here’s a simple summary:

Key Differences Between Shinto Shrines and Buddhist Temples

| Feature | Shinto Shrine | Buddhist Temple |

|---|---|---|

| Religion | Shinto (Japan’s indigenous belief) | Buddhism (from India via China/Korea) |

| Deities Worshipped | Kami (gods/spirits of nature) | Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, other figures |

| Main Gate | Torii gate | Sanmon gate |

| Prayer Style | Two bows, two claps, one bow | Bow once, press palms together (gassho) |

| Ritual Language | Norito (Shinto ritual prayers) | Sutras and Buddhist scriptures |

In the end, both shrines and temples offer unique insights into Japanese spirituality and tradition.

You don’t need to choose one over the other — visiting both will give you a deeper appreciation of Japan’s rich cultural heritage.

What matters most is your respect, sincerity, and open heart as a visitor.

And if you happen to mix things up — like clapping at a temple or forgetting to bow at a shrine — that’s okay, too.

The gods and Buddhas are probably more forgiving than you think.