Located in the heart of Asakusa, Tokyo, Sensō-ji is the city’s oldest and most iconic Buddhist temple. Founded in 628, it offers visitors a unique combination of spiritual tradition, historical architecture, and vibrant street life.

Whether you’re interested in exploring Japan’s Buddhist roots, capturing striking photos of its famous red lantern, or simply enjoying traditional street snacks and souvenirs, Sensō-ji is a must-visit destination for both first-time and returning travelers.

How to Get to Sensō-ji Temple

Sensō-ji is easily accessible from several train and subway lines.

From any of these stations, follow signs toward Kaminarimon Gate. The giant red lantern is hard to miss and will lead you directly into the heart of the temple grounds.

Opening Hours, Entrance Fee & Useful Info

The Asakusa Culture and Tourist Information Center, located right across from Kaminarimon, provides English-speaking staff, free maps, Wi-Fi, and luggage storage.

You can also find multilingual brochures and signage throughout the temple area.

The History of Sensō-ji

Sensō-ji’s story begins in the year 628, when two fishermen discovered a statue of Kannon, the goddess of mercy, in the Sumida River.

A local elder recognized its significance and enshrined the statue in his home, forming the foundation of what would become Sensō-ji Temple.

Over the centuries, the temple received patronage from influential figures, including shoguns like Tokugawa Ieyasu, solidifying its place as a center of Buddhist worship in Tokyo.

Although much of the temple was destroyed during World War II, it was carefully rebuilt in traditional style using modern materials, preserving its cultural heritage.

What to See at Sensō-ji

Sensō-ji offers more than just one landmark—it’s a rich, immersive space filled with history, culture, and spiritual moments.

From the striking gates and towering pagoda to the bustling shopping streets and interactive rituals, each part of the temple grounds tells a story.

As you explore, you’ll find places to admire, reflect, participate, and even take home a bit of wisdom or good fortune.

Here’s a closer look at some of the highlights that make Sensō-ji such a memorable destination.

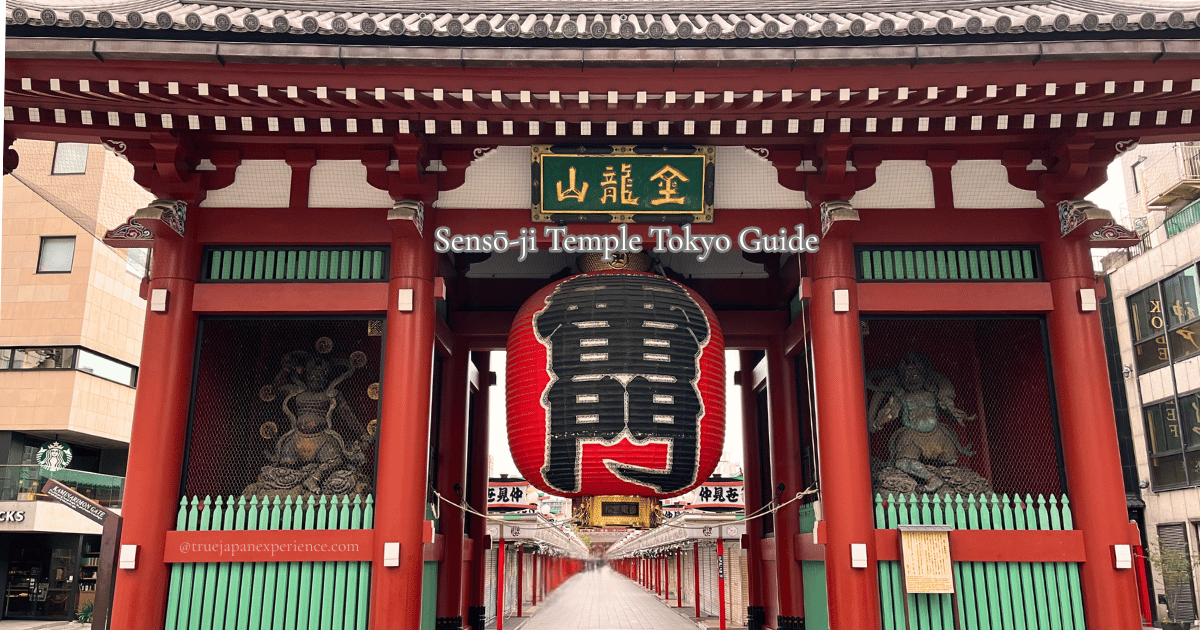

Kaminarimon (Thunder Gate)

Kaminarimon, or the “Thunder Gate,” is the grand outer gate that welcomes visitors to Sensō-ji Temple. With its bold red color, towering presence, and giant paper lantern, it’s one of the most iconic and photographed landmarks in all of Tokyo.

The gate was originally built in the year 942, but it has been destroyed and rebuilt several times throughout history. The current structure dates back to 1960 and was donated by Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of Panasonic, as an act of devotion after recovering from illness.

Hanging in the center is a massive red lantern, over 3 meters tall and weighing about 700 kilograms. It’s inscribed with the characters 雷門 (Kaminarimon), meaning “Thunder Gate.” The lantern symbolizes protection from storms and disasters, both literal and spiritual.

On either side of the gate stand two imposing statues: Fūjin, the god of wind, and Raijin, the god of thunder. These guardian deities are believed to ward off evil and protect the temple from harm.

Passing under Kaminarimon isn’t just a photo opportunity—it’s a symbolic step into a sacred space. From here, you’ll be guided into Nakamise Street and toward the heart of Sensō-ji.

Nakamise Shopping Street

After passing through Kaminarimon, you’ll enter Nakamise-dōri, a lively shopping street that stretches for about 250 meters, leading directly to the temple’s inner gate, Hōzōmon. It’s one of Japan’s oldest shopping streets, with roots tracing back to the early 18th century.

Historically, the street was lined with vendors who were granted permission to sell goods to temple visitors in exchange for helping to keep the temple grounds clean. Over the centuries, it evolved into a bustling center of commerce and culture, serving both worshippers and tourists alike.

Today, Nakamise is home to nearly 90 shops offering a colorful mix of traditional crafts, Japanese souvenirs, and street food snacks. You can find everything from folding fans and yukata to maneki-neko figurines, daruma dolls, and classic sweets like ningyō-yaki and senbei rice crackers.

The atmosphere is lively and full of energy, especially on weekends and holidays. Yet despite the crowds, the street retains a uniquely nostalgic charm, with shopfronts that evoke the Edo period and a strong sense of continuity with the past.

Whether you’re looking to try a matcha treat, browse handmade souvenirs, or simply enjoy the festive spirit, Nakamise Street is a perfect place to take your time before entering the sacred space of Sensō-ji.

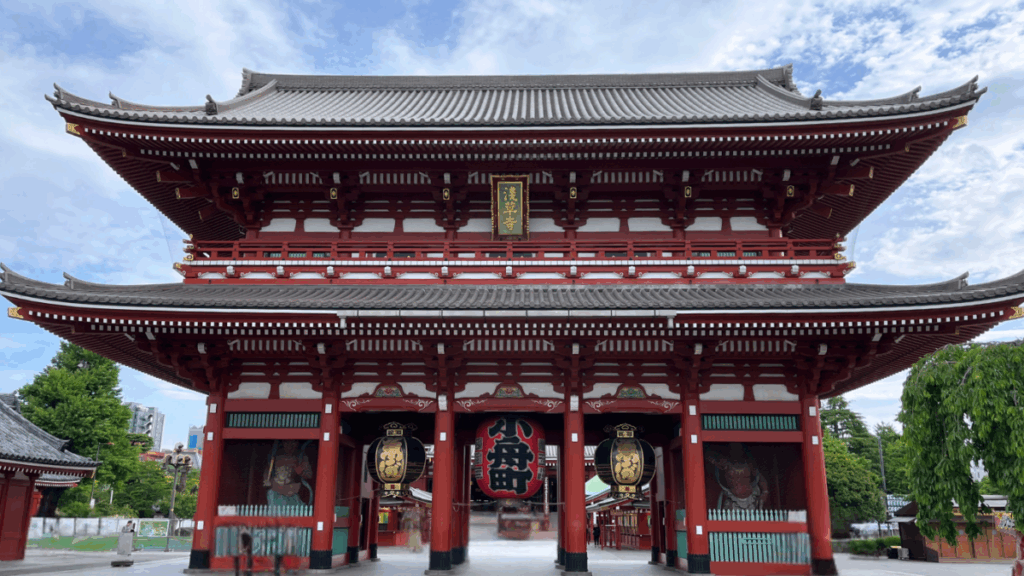

Main Hall (Hondō)

The main hall, or Hondō, is the spiritual heart of Sensō-ji Temple. This is where visitors offer prayers to Kannon Bosatsu (also known as Avalokiteśvara), the bodhisattva of compassion who has been worshipped here for over 1,300 years.

The current structure was completed in 1958, after the previous hall was destroyed during World War II. Although it was rebuilt using reinforced concrete for safety and durability, the design faithfully follows traditional Edo-period architectural styles, preserving the visual and spiritual essence of the original.

Inside, the main object of worship is a statue of Kannon, said to have been miraculously found by two fishermen in the Sumida River in the year 628. The statue is classified as a hibutsu—a “hidden Buddha”—which means it is not displayed to the public. Even the temple’s head priests do not view it directly. A representation of the statue is shown in front of the inner sanctuary for worshippers.

The building features a majestic tiled roof with curved eaves, wooden-style detailing, and vibrant traditional colors. The overall atmosphere is solemn yet welcoming, and the scent of incense and soft chants often fill the air.

Visitors come to the main hall to pray for everything from health and safety to academic success, love, and personal guidance. Whether or not you are religious, standing before the Hondō offers a moment of quiet reflection and connection with centuries of devotion.

Five-Story Pagoda

Standing gracefully to the west of the main hall, the Five-Story Pagoda is one of Sensō-ji’s most elegant and symbolic structures. At approximately 53 meters tall including its base, it adds a vertical sense of serenity and spiritual grandeur to the temple grounds.

The original pagoda was built in the year 942 by military leader Taira no Kimimasa. Over the centuries, it was destroyed and rebuilt several times due to fires, earthquakes, and wartime bombing. The current structure was reconstructed in 1973, using steel and reinforced concrete for durability, while maintaining the classic beauty of traditional Japanese architecture.

Each of the five tiers represents one of the five elements in Buddhist cosmology: earth, water, fire, wind, and void (or sky). At the top is a sōrin, a spire-like finial that includes sacred ornaments and serves as a spiritual antenna.

Inside the topmost level of the pagoda is a reliquary containing a bone fragment of the Buddha, gifted by Sri Lanka’s Isurumuniya Temple. Although the interior is not open to the public, the pagoda remains an important symbol of Buddhist faith and international connection.

In 2017, the roof tiles were replaced with titanium tiles, combining traditional appearance with modern weather resistance—ensuring the pagoda’s graceful form can be preserved for future generations.

Whether viewed up close or as part of the skyline behind the temple, the Five-Story Pagoda adds a sense of timeless beauty and sacred elevation to your visit.

Incense Burner

In front of the main hall at Sensō-ji, you’ll see a large incense burner called the jōkōro (常香炉). This is where visitors offer incense sticks and gather around the smoke rising from the burner—a practice deeply rooted in Japanese temple culture.

The smoke is believed to have purifying and healing effects. Many people wave it over parts of their body that feel weak or unwell, with the hope of improving recovery or promoting better health.

There’s also a popular belief that waving the smoke toward your head can “make you smarter” or “help you think more clearly.” These ideas have been passed down through generations and are embraced by locals and tourists alike.

This ritual is often done before praying at the main hall, as a way to cleanse the body and mind and show respect before approaching the sacred space.

It’s one of the most memorable and interactive parts of a visit to Sensō-ji, and a beautiful example of how tradition and everyday practice come together.

Omikuji

You can also draw a paper fortune, or omikuji, near the main hall. It’s a fun and traditional experience, but be prepared—Sensō-ji is known for giving a surprisingly high number of “bad luck” slips (凶 / kyō).

This isn’t by mistake. Sensō-ji follows an old system called Kannon Hyaku-sen (観音百籤), a traditional method of divination passed down from the Edo period.

While many modern temples and shrines reduce the number of bad fortunes to avoid discouraging visitors, Sensō-ji has preserved the original balance, making it one of the most honest and unfiltered omikuji experiences in Japan.

Because of this, some people say the fortunes here are “more accurate” or “stricter.”

But if you draw a bad fortune, don’t worry—it’s not all doom and gloom. In Japanese belief, a bad fortune can mean:

“Things can only get better from here.”

“Now is a time to be cautious and reflect.”

If you receive a bad fortune, many visitors choose to tie it to the designated racks in the temple grounds, hoping to leave the bad luck behind.If it’s a good one, people often take it home with them as a lucky charm—but it’s entirely up to you.

Wearing a Kimono Around Sensō-ji

Wearing a kimono in Asakusa is one of the most popular activities for international visitors. Many rental shops near the temple offer full dressing services with English support.

・Strolling in a kimono adds a traditional charm to your visit

・Perfect for memorable photos in front of the temple or pagoda

・Online reservations are recommended, especially during holidays

If you’re interested in Japanese culture, this is one of the easiest and most rewarding ways to experience it.

Street Food and Snacks Near the Temple

Nakamise Street and its nearby alleys are full of delicious treats.

Though shops may change frequently, here are some perennial favorites:

・Asakusa Menchi – Juicy fried meat croquette

・Jumbo Melon Pan – Giant fluffy sweet bun

・Ningyō-yaki – Small sponge cakes shaped like temple symbols

・Matcha ice cream & seasonal sweets – Instagram-worthy and refreshing

You’ll always find something new to try, especially when exploring in a yukata or kimono.

New and creative snacks are constantly appearing, so part of the fun is seeing what unique treats await you on your next visit.

At the same time, you’ll find traditional Japanese confections that have been loved in Asakusa for generations—offering a sweet taste of local history.

Best Photo Spots Around Sensō-ji

Sensō-ji is not only a place of worship—it’s also one of the most photogenic spots in Tokyo.

With its iconic gates, traditional architecture, and lively shopping streets, the temple and its surroundings offer a variety of picture-perfect scenes throughout the day.

Whether you’re capturing the calm of the early morning or the energy of the crowds, here are some recommended locations to frame your memories of Asakusa.

・Kaminarimon Gate – With its iconic red lantern

・Nakamise Street – Bustling with colorful shops and traditional architecture

・Five-Story Pagoda – Beautiful in the afternoon light or illuminated at night

・Denboin Garden – A peaceful Japanese garden open seasonally

・Sumida Park & Azuma Bridge – Offering views of the Skytree and Sumida River

For the best photos, visit early in the morning when the light is soft and the crowds are thin.

That said, the lively crowds along Nakamise Street during the day can also make for a memorable and energetic shot—capturing the true spirit of Asakusa.

Seasonal Events and Festivals

Sensō-ji hosts events year-round, but the most famous is the Sanja Matsuri in May. This vibrant festival features:

・Traditional mikoshi (portable shrines)

・Processions through the streets of Asakusa

・Live performances and street food stalls

Other seasonal events include New Year temple visits, cherry blossom season in spring, and light displays in winter. Be sure to check the temple’s official website or tourist guides before your trip.

A Quick Note on the Name: Why “Sensō-ji” and Not “Asakusa-dera”?

In Japanese, the temple’s name is written as 浅草寺, and it’s read Sensō-ji.

The first two characters, 浅草, are the same ones used in the name of the surrounding neighborhood and train station—where they are read Asakusa.

So why is the temple called Sensō-ji, not Asakusa-dera, even though it uses the same kanji?

The answer lies in how kanji are read in Japanese. There are two main types of readings:

・Kun’yomi – the native Japanese reading, typically used for place names and Shinto shrines

・On’yomi – a reading derived from Chinese pronunciation, commonly used for Buddhist temples

Since Buddhism was introduced to Japan through China, temple names are usually read using the on’yomi. That’s why 浅草寺 is pronounced Sensō-ji instead of Asakusa-dera.

There are exceptions, such as 清水寺 (Kiyomizu-dera) and 鞍馬寺 (Kurama-dera), which use kun’yomi. But Sensō-ji is a classic example of the on’yomi tradition in temple naming.

It’s a small detail, but one that reveals how deeply Japanese religion, language, and history are intertwined.