Japanese food is loved around the world—but what truly defines traditional Japanese cuisine?

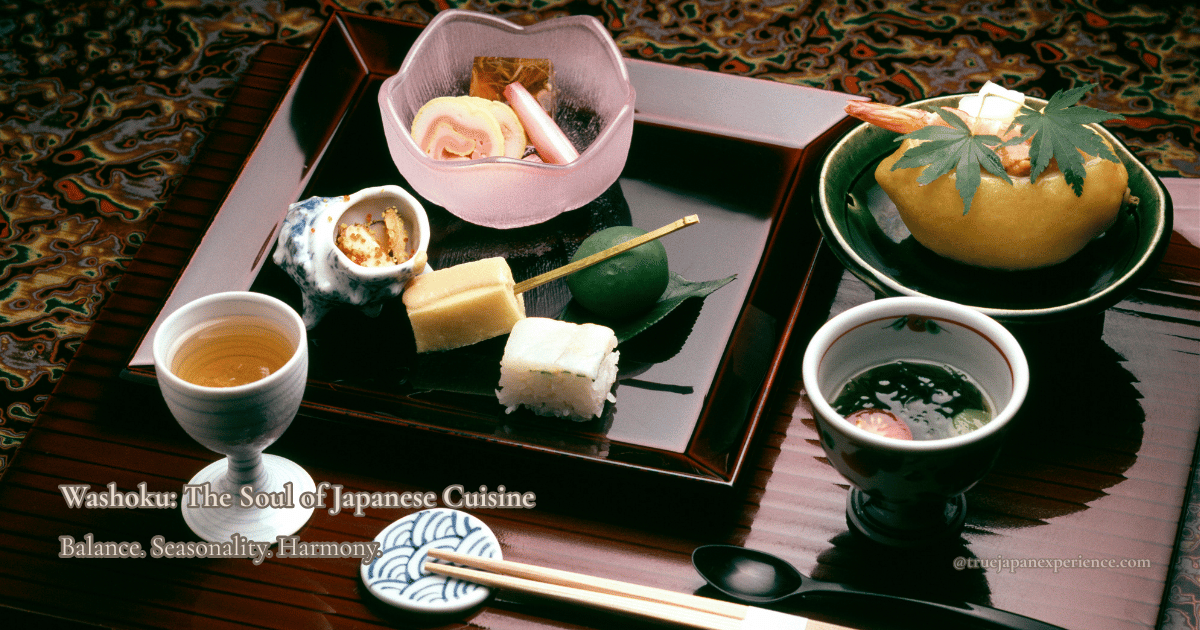

Known as washoku, this unique food culture is deeply rooted in seasonality, harmony, and respect for nature.

Before diving into popular dishes or regional specialties, let’s explore what washoku really means and why it has been honored on the world stage.

What Is Washoku? A UNESCO-Recognized Cultural Heritage

Osechi ryori, the traditional New Year’s meal in Japan, reflects seasonal beauty and cultural meaning.

Washoku refers to traditional Japanese cuisine, and in 2013, it was recognized as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage.

This recognition is not just for the food itself but for the entire cultural context it represents—respect for nature, seasonality, family traditions, and communal celebration.

Washoku is not just about what is eaten. It reflects how food is prepared, shared, and appreciated, especially during seasonal events like New Year’s (Osechi), Hina Matsuri (Girls’ Festival), or even everyday meals that align with nature’s rhythms.

The Core of Washoku: Health, Balance, and Aesthetic Harmony

At the heart of washoku lies a deep commitment to health, nutritional balance, and visual beauty.

Rather than relying on rich sauces or heavy portions, traditional Japanese meals emphasize variety, moderation, and mindfulness. This philosophy is perhaps best seen in the concept of ichiju sansai.

Ichiju Sansai: The Foundation of Balance

A typical Japanese breakfast of steamed rice and miso soup—balanced and comforting.

One of the pillars of washoku is the “ichiju sansai” style—”one soup and three dishes.” This basic structure includes:

・A bowl of rice (main staple)

・A soup (typically miso soup)

・One main dish (meat or fish)

・Two side dishes (vegetable-based or pickled items)

This format ensures a nutritious, low-fat, and low-calorie meal that is rich in vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber.

One common way this balance appears in daily life is through teishoku, or set meals. Typically served at lunch spots or casual restaurants, a teishoku includes rice, miso soup, a main dish (such as grilled fish or tonkatsu), and side dishes like pickled vegetables or salad.

Affordable, nutritious, and satisfying, teishoku reflects the ichiju-sansai principle and remains a popular choice for everyday dining in Japan.

Seasonal Ingredients and Visual Appeal

Kaiseki cuisine—a multi-course meal celebrating the balance and seasonality of Japanese food.

Washoku emphasizes using seasonal and local ingredients.

Meals are carefully planned to align with the time of year, incorporating flavors and ingredients that reflect nature’s cycle—from bamboo shoots in spring to mushrooms in autumn.

The plating and presentation are equally important, reflecting the beauty of nature and the changing seasons. The use of specific dishes, colors, and garnishes is not just for decoration, but to evoke a sense of place and time.

For example, a summer meal may be served on cool blue porcelain to suggest refreshing water, while autumn dishes may feature warm hues and leaf motifs to match the falling foliage.

This mindful attention to detail turns every meal into a multisensory experience—one that delights not only the palate but also the eyes and heart.

Dashi and the Essence of Umami

Freshly poured dashi, the heart of umami in Japanese cuisine.

Japanese cuisine utilizes dashi (broth made from kombu kelp, bonito flakes, or dried sardines) to create umami, the “fifth taste.”

This technique allows for flavorful dishes without relying heavily on salt or fats. Dashi is a cornerstone of Japanese soups, simmered dishes, and sauces.

While dashi is used throughout Japan, its importance and character vary by region. Nowhere is this more evident than in Kansai, where the cuisine places a strong emphasis on subtle, refined flavors drawn from high-quality kombu. Compared to the bolder, soy sauce-heavy flavors of the east, Kansai dishes often appear lighter in color but are rich in umami, allowing the natural taste of the ingredients to shine.

This regional contrast sets the stage for exploring Japan’s diverse culinary identities.

The Five Techniques of Washoku: Simplicity and Depth

A typical teishoku set meal, offering a balanced combination of rice, soup, and assorted side dishes.

Washoku employs five main cooking methods known as “gohō”:

・Raw (Nama) – Slicing fresh seafood or vegetables (e.g., sashimi)

・Boiled (Niru) – Cooking in broth or sauces to bring out umami (e.g., nimono)

・Grilled (Yaku) – Enhancing flavor through searing or grilling (e.g., yakizakana)

・Steamed (Musu) – Gentle cooking using steam (e.g., chawanmushi)

・Fried (Ageru) – Deep-frying for contrast in texture (e.g., tempura)

These methods are often combined within a single meal to provide variety in taste, texture, and nutrition.

The Evolution of Eating Habits in Japan

Western fast food has become a common part of everyday life in Japan, especially among younger generations.

In recent decades, Japan’s food culture has evolved significantly to meet the demands of modern lifestyles.

With more people leading busy lives, there has been a steady rise in the consumption of convenience foods—such as frozen meals, pre-cut vegetables, and ready-to-eat retort pouches. These options help families save time and reduce the burden of daily cooking.

The influence of globalization and the proliferation of fast food chains and convenience stores have also introduced a wide variety of Western dishes into the everyday Japanese diet.

Hamburgers, pizza, fried chicken, and sandwiches are now common in both restaurants and homes, coexisting with traditional Japanese meals.

At the same time, growing awareness of health and nutrition has led to a surge in demand for low-sodium, high-fiber, and well-balanced food options.

Many meals are now designed for single servings, reflecting the increasing trend toward individual dining (known as koshoku) among all age groups. This shift shows how Japan continues to balance tradition with modern needs, creating a uniquely adaptive food culture.

While traditional meals like teishoku (set meals) remain popular, modern influences—especially Western fast food—have shifted the eating habits of younger generations.

Many opt for quick and convenient meals, but as people age, there is a notable return to traditional Japanese food for its perceived health benefits and emotional comfort.

Regional Diversity: Flavor and Identity Across Japan

Japan’s culinary landscape changes dramatically from north to south. Each region has developed its own food culture, shaped by climate, available ingredients, and historical influences.

From delicate flavors in the west to bolder seasoning in the east, these regional differences reflect the country’s rich culinary identity.

Hokkaido

Jingisukan, Hokkaido’s signature lamb dish, is enjoyed grilled over a dome-shaped iron pan with fresh vegetables.

Japan’s northern frontier, Hokkaido offers fresh seafood and hearty fare to match its cold climate.

・Rich in fresh seafood, dairy, and root vegetables

・Warming dishes to suit the cold climate

・Signature dishes: Ishikari-nabe, Soup Curry, Jingisukan (grilled lamb)

Hokkaido’s cuisine is wholesome, filling, and deeply satisfying.

Tohoku (Northeast)

Known for its cold winters and abundant natural resources, Tohoku cuisine emphasizes hearty, warming dishes.

・Cold climate favors preserved foods and hearty stews

・Bold flavors using miso and salt

・Signature dishes: Senbei-jiru (Aomori), Kiritanpo-nabe (Akita), Wanko-soba (Iwate)

Tohoku’s food is both comforting and deeply tied to its rugged landscapes.

Kanto (East)

Edomae sushi, a culinary hallmark of Tokyo, highlights the simplicity and freshness of Kanto cuisine.

The political and economic center of Japan, Kanto is famous for its bold urban flavors and Edo-period culinary traditions.

・Home of Edo-style sushi tradition

・Rich in seafood, uses dark soy sauce

・Signature dishes: Edomae-zushi, Namero (Chiba), Monjayaki (Tokyo)

Kanto’s cuisine is robust, reflecting its bustling metropolitan character.

Chubu (Central)

Stretching across mountains and coastlines, Chubu offers a diverse blend of inland and maritime influences.

・Diverse terrain supports both rice and wheat cultures

・Known for miso-based dishes and mountain vegetables

・Signature dishes: Hōtō (Yamanashi), Miso-nikomi Udon (Aichi), Ise Udon (Mie)

Chubu’s regional dishes reveal a balance between rustic simplicity and rich flavor.

Kansai (West)

Okonomiyaki, a savory pancake from Osaka, rich in flavor and culture.

Once the cultural heart of Japan, Kansai is known for its refined tastes and emphasis on presentation.

・Focus on dashi and subtle flavoring with light soy sauce

・Highly aesthetic presentation

・Signature dishes: Takoyaki, Okonomiyaki (Osaka), Yudofu (Kyoto), Akashiyaki (Hyogo)

Kansai cuisine highlights elegance, umami, and culinary artistry.

Interestingly, people from Kansai often find food in Tokyo overly salty or heavy, while Tokyoites may feel Kansai flavors are too mild.

This is more than just regional pride—popular products like Nissin Donbei and Maruchan Akai Kitsune even use different soup bases to suit the taste preferences of eastern and western Japan.

Chugoku & Shikoku

These regions boast rich natural bounty from the Seto Inland Sea and a history of regional variety.

・Abundance of seafood from Seto Inland Sea

・Varied seasoning—miso, soy, and sweet-savory blends

・Signature dishes: Anago-meshi (Hiroshima), Sanuki Udon (Kagawa)

The flavors here are diverse, reflecting coastal traditions and regional ingenuity.

Sanuki udon, known for its chewy texture and refined simplicity, represents Shikoku’s culinary style.

Kyushu

With its warm climate and historical trade links, Kyushu cuisine is bold and soulful.

・Influenced by tropical climate and historical trade

・Sweet soy-based seasoning with strong umami

・Signature dishes: Tonkotsu Ramen (Fukuoka), Champon (Nagasaki), Chicken Charcoal Grill (Miyazaki)

Kyushu’s dishes are rich, flavorful, and unforgettable.

Okinawa

Okinawan cuisine blends indigenous ingredients with foreign influences, creating a unique food culture.

・Tropical ingredients like goya, papaya, and island tofu

・Heavy use of pork, often cooked whole

・Cultural fusion of Chinese, Japanese, and American influences

・Signature dishes: Goya Champuru, Rafute, Okinawa Soba

The island’s food is vibrant and deeply rooted in its multicultural past.

Goya champuru is a classic Okinawan home-cooked dish made by stir-frying bitter melon with tofu, egg, and pork (or sometimes Spam).

While these regional traditions remain strong, it’s also worth noting that restaurants, izakaya, and convenience stores across Japan tend to favor bolder, saltier flavors today—regardless of location.

Conclusion

Washoku is more than a meal—it is a lens through which you can view Japan’s geography, culture, and values. Whether you’re exploring the refined flavors of Kyoto or sampling hearty seafood stews in Hokkaido, every dish tells a story.

Understanding washoku means appreciating the balance between flavor, nutrition, beauty, and seasonal life. Next time you’re in Japan, let your tastebuds travel the regions—and discover the deeper meaning of every bite.