Japanese New Year is called お正月 (Oshogatsu). It is the most important holiday for Japanese people.

Most Japanese spend this time with family, following old traditions and eating special foods.

For visitors, Japanese New Year is a rare chance to see a different side of the country—peaceful, full of ritual, and rich with meaning.

What is Japanese New Year?

Japanese New Year, called お正月 (Oshogatsu), is the most important holiday period in Japan. The word “Oshogatsu” originally means “the first month of the year.”

People celebrate the beginning of a new year, usually from January 1st to January 3rd.

During this time, families welcome a special New Year god called 年神様 (Toshigami-sama) into their homes. People pray for health, happiness, and a good harvest for the year.

Today, it is a special time when families and close friends celebrate the new year together, give thanks for being healthy and safe, and wish for even better times ahead.

This is why Japanese New Year is not just about parties; it is about family, respect, and starting fresh for the future.

Preparing for Japanese New Year

In Japan, preparations for the New Year usually start on December 13th. This day is called 正月事始め (Shogatsu Kotohajime), the traditional beginning of New Year preparations.

From this day, families begin a big cleaning of their homes, called 大掃除 (Oosouji), and get ready to welcome the New Year god.

In many homes, these preparations continue step by step from mid-December, and most are finished by the last day of the year. As the New Year gets closer, everyone in the family joins in to prepare for a happy and fresh start.

Now let’s take a closer look at how people in Japan prepare for the New Year.

Cleaning the House (大掃除 Oosouji)

At the end of the year, Japanese families do a deep cleaning called Oosouji, which means “big cleaning.”

This is not like regular cleaning. People clean every corner of the house very carefully. They remove dust from windows, walls, floors, and even behind furniture.

This big cleaning is an old tradition that helps prepare the home to welcome the New Year god, called Toshigami-sama.

The tradition started a long time ago, during the Heian period (more than 1,000 years ago). It was first done in the Imperial Palace and then spread to temples, shrines, and people’s homes.

The purpose of Oosouji is to clean away the dirt, dust, and bad energy from the old year and make room for new luck and happiness.

In this cleaning, people also organize their belongings. They throw away things they do not need anymore to make the home tidy and fresh. Many families start this cleaning around December 13th, a day called Shogatsu Kotohajime, and finish before the New Year begins.

Family members often work together on Oosouji. Today, it is still very important to Japanese people because it shows respect for their home and brings a fresh start for the new year.

Japanese New Year Decorations

During the Japanese New Year, people prepare special decorations to welcome the New Year god and bring good luck.

These decorations are usually made or bought starting from December 13th which means the beginning of New Year preparations.

Most families start putting up their decorations between late December, often around December 26th to 28th. It is important to avoid putting up decorations on December 29th or 31st because these days are considered unlucky.

The decorations stay up until early January, usually until January 7th or sometimes January 15th, depending on the region.

Now, let’s learn more about what these decorations look like and what they mean.

Kadomatsu (門松)

Kadomatsu is a decoration made mainly from pine branches and bamboo sticks bound with straw ropes. It stands in pairs outside the front door or gate.

Pine trees stay green all year and show strength and life. Bamboo grows fast and straight, symbolizing honesty and a strong spirit.

These decorations mark that the place is ready and welcoming for the Toshigami-sama, the New Year god who brings good luck.

Shimekazari (しめ飾り)

Shimekazari is a special rope made from rice straw. It hangs above the front door or in a visible place at home.

Shimekazari shows that the house is clean and ready to welcome good spirits while keeping bad spirits away.

In the past, people often cleaned their cars carefully and decorated them with shimekazari during the New Year. You could see many cars with these decorations. However, today it is rare to see cars with shimekazari, as this tradition has mostly disappeared.

Kagami Mochi (鏡餅)

Kagami mochi looks like two round rice cakes stacked, with a small orange (called daidai) on top.

The round shape represents the idea of harmony and the circle of life. The rice cakes come from the previous year’s rice harvest, so showing thanks for the food is part of the meaning.

The orange symbolizes the hope for a long family life that lasts many generations. Usually, kagami mochi is placed in a special spot inside the home, like an altar or a decorated shelf.

These three decorations are important symbols in Japanese New Year celebrations. They invite happiness, health, and success to the family for the coming year.

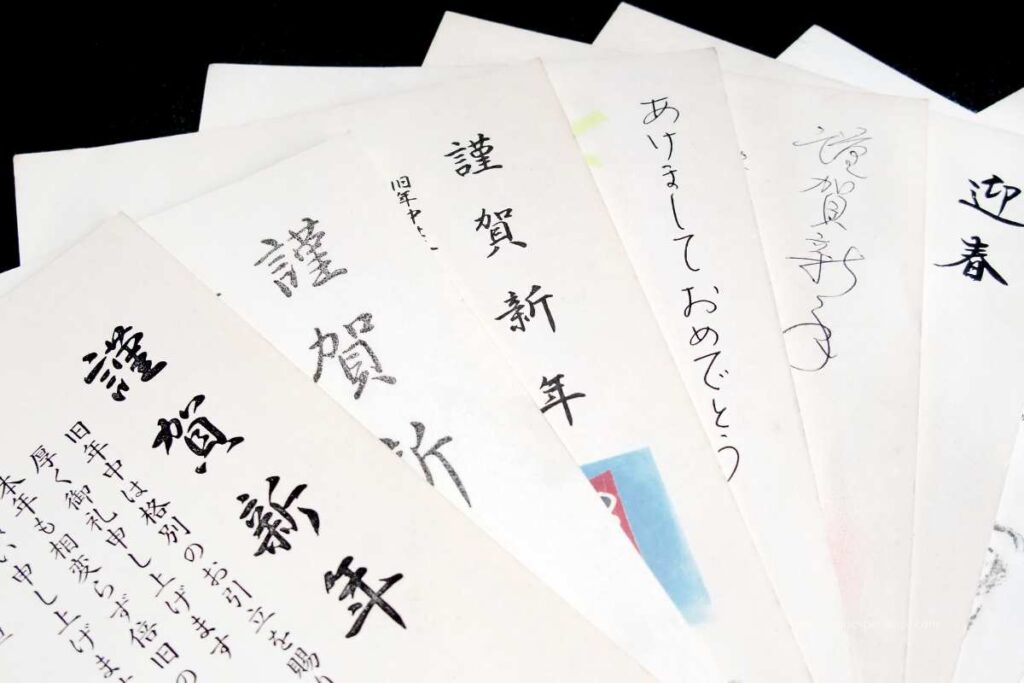

Japanese New Year Greeting Cards (年賀状 Nengajo)

In Japan, people also prepare special New Year greeting cards called Nengajo. Nengajo are written in late December and sent so they arrive on or just after New Year’s Day. People usually start sending them from December 25th to make sure they arrive on time.

In Western countries, Christmas cards often say “Merry Christmas and Happy New Year.” But in Japan, Christmas is not a traditional holiday, so it is not common to send Christmas cards.

Instead, Japanese people send Nengajo not only to family but also to friends, coworkers, and people who have helped or taken care of them during the past year. This includes relatives or friends who live far away and are difficult to see often. Sending a Nengajo is a way to show thanks and keep good relationships, even if you cannot meet in person.

However, in recent years, fewer people send Nengajo by mail. Many now use social media or email to send New Year greetings because it is faster and easier. Still, many people like sending physical Nengajo because it shows care and is a special Japanese tradition.

Sending Nengajo is a way to keep up relationships and show respect. Even though the way people connect has changed, the meaning of wishing a happy and healthy new year stays important in Japanese culture.

New Year’s Eve (December 31)

On the last night of the year, families eat 年越しそば (Toshikoshi Soba), long buckwheat noodles. The long noodles mean a wish for long life and a clean break from the old year.

At midnight, Buddhist temples ring bells 108 times (除夜の鐘 Joya no Kane). This number is based on old beliefs about the “108 troubles” of humans. The bells clean away the bad feelings from the past year.

On New Year’s Eve, many families watch a famous music show on TV called “Kohaku Uta Gassen.” This show is very popular and usually lasts until late night.

Around the time when “Kohaku” is ending, you may start to hear the sound of the temple bells called “Joya no Kane” far away. The bells are rung slowly and softly as people prepare to welcome midnight.

When the bell rings for the last time, it is midnight and the New Year has officially begun. This moment is very special and peaceful in Japan, marking the end of the old year and the start of the new one.

Japanese New Year: Customs and Activities

In Japan, New Year is one of the most exciting times of the year! It’s a season for family, friends, and fresh beginnings. People share good wishes and visit shrines to pray for luck and happiness.

Let’s explore a few of these lovely New Year traditions together.

New Year Greetings in Japan

In Japanese New Year greetings, people first say “Akemashite omedetou gozaimasu” (あけましておめでとうございます), which means “Happy New Year.”

After that, they say “Kotoshi mo yoroshiku onegaishimasu” (今年もよろしくお願いします). This phrase means “Please take care of me this year too” or “Let’s have a good year together.”

Different greetings are used depending on who you are talking to, such as family, friends, or work colleagues. Some greetings are very polite and used when speaking to people in higher positions, like bosses or teachers.

First Shrine Visit (初詣 Hatsumode)

Hatsumode is the first visit to a shrine or temple after the New Year begins. People go to these places to pray for a good year and to give thanks for the past year.

The time for Hatsumode can be different depending on where you live in Japan. In the Kanto region (around Tokyo), people usually go before January 7th. In the Kansai region (around Kyoto and Osaka), it is common to visit until January 15th. But no matter where you live, it is good to go before Setsubun, which is around February 3rd.

When you choose a shrine or temple for Hatsumode, it is important to visit the one that protects your area. This is called your 氏神様(Ujigami), the local guardian god. Some people also visit the temple where their family’s ancestors are remembered, called a 檀家寺(Danka-dera).

There is no strict rule about where you must go. Others choose a place depending on where the lucky direction (恵方

Ehou) of the year is, or where they believe their wishes will be answered.

Famous shrines like Meiji Shrine in Tokyo, Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto, and Sumiyoshi Taisha in Osaka have more than two million visitors during the first three days of the New Year alone. These places are very busy but full of happy people celebrating Hatsumode.

Traditional Japanese New Year Dishes

In Japan, the New Year wouldn’t be complete without delicious traditional foods! These dishes are not just tasty—they also bring good luck and happy wishes for the year ahead.

Let’s explore a few of the most loved New Year dishes.

Osechi Ryori

Osechi ryori is a special kind of food that Japanese people eat to celebrate the New Year. These dishes are packed neatly into beautiful boxes called jubako. The boxes show a wish for good things to pile up, like happiness and luck.

Osechi dishes are also an offering to the New Year god, called 年神様(Toshigami-sama). After the god receives the food, families eat the dishes together. That is why osechi uses foods that keep well and taste good even when cold.

Each food in osechi has a special meaning. For example, black beans mean working hard and staying healthy. Herring roe symbolizes many children and family growth.

Long ago, many families made osechi by hand, but now most people buy them from stores or order them online. The styles are also changing, with Western and Chinese style osechi becoming popular.

Ozoni

Ozoni is a soup with rice cakes called mochi, vegetables, and sometimes chicken or fish. It is a traditional New Year’s dish in Japan. The soup and mochi shapes can be different depending on where you live and your family’s style.

Ozoni started as a special food to share with the gods to thank for a good harvest and to pray for family safety.

The rice cakes in ozoni are important. Round mochi are often used to wish for family happiness. Square or square-edged mochi sometimes are used because the word for “square” sounds like “defeat,” meaning to overcome enemies.

Common vegetables in ozoni are radish, carrot, taro, and leafy greens. The taste of the soup also changes by region. In eastern Japan, soy sauce clear soup is usual; in western Japan, miso soup is more common.

Spending New Year in Japan

In Japan, New Year is the most important holiday of the year. Many offices and shops close, and people travel back to their family homes. It is a time to rest, meet relatives, and welcome the new year together.

Families usually eat osechi ryori, a special set of dishes prepared only for New Year.

Another big tradition is hatsumode, the first visit to a shrine or temple. People go with family or friends, pray for good fortune, and sometimes buy charms or draw omikuji (fortune slips).

Of course, not everything is formal. Many people also spend time relaxing at home. They watch New Year’s TV shows, play board games, or just enjoy being with family.

In the past, children played games like fukuwarai (a funny face game), hanetsuki (a paddle game), or flew kites. These are less common today, but they are still part of the memory of Japanese New Year.

For Japanese people, New Year is not only about celebration, but also about connection. It is a chance to be with family, start fresh, and feel thankful for the year ahead.

Japanese New Year: Quiet Streets and Local Travel

During the Japanese New Year, the mood in the country feels very different than usual.

In big cities like Tokyo, many people travel back to their hometowns to be with family, or they go on trips together. Because of this, cities that are usually busy and crowded suddenly become quiet.

Many shops, restaurants, and even offices close for the holiday, usually from January 1 to January 3. Even trains and buses may be less full than usual, except for those going toward sightseeing spots or rural areas.

In smaller towns and the countryside, the effect is even stronger. Most local stores and cafes close. Travelers visiting rural Japan may find almost everything shut, so planning is important.

In Japan, New Year’s is celebrated at home with family, or at a traditional Japanese inn, where people enjoy delicious food and hot springs in a quiet atmosphere.

New Year’s is not about big parties or loud celebrations, but rather a time to relax and spend time with loved ones.

Tips for Foreign Visitors

・Plan ahead: Many businesses are closed. Research and check online in advance before going out.

・Book hotels and trips early: New Year is peak travel season for Japanese families, so popular inns and hotels can be fully booked far in advance.

・Try traditional food: If invited by a Japanese friend, or if staying at a traditional inn, try おせち料理 (Osechi Ryori) and お雑煮 (Ozoni). These are special foods for the New Year.

・Be careful at popular shrines: Avoid big and famous shrines and temples, especially on January 1. Crowds can be huge and sometimes people have to push to get inside. If you want to try 初詣 (Hatsumode), choose a smaller, local shrine for a safer and calmer experience.

・Enjoy the peaceful atmosphere: The quiet and calm feeling of Japan during these days is very special. Walk around and see another side of the country not usually visible.

If you know what to expect, the Japanese New Year can be a beautiful and relaxing time to experience local life in a very different mood than usual.

Conclusion: A Fresh Start with Warm Traditions

The Japanese New Year is more than just a holiday—it’s a time to refresh your heart and start again.

Families come together, share food, visit shrines, and show kindness to each other. Every custom, from Osechi Ryori to Hatsumode, has a warm meaning that connects people.

May your New Year be full of joy, peace, and new beginnings!

Want to enjoy the Japanese New Year comfortably?

Check our guide on Japan Winter Weather: What to Expect and What to Wear to find the best clothes for the season.